In the distant past, when Assyria still reigned supreme, two tribes of nomadic horsemen wreaked havoc across Asia. They were known as the Cimmerians and the Scythians.

The Cimmerians lived on the steppes north of the Black Sea until they were driven from their homeland by the Scythians, who had themselves been driven from their own homeland in Central Asia by the nomadic Massagetae.

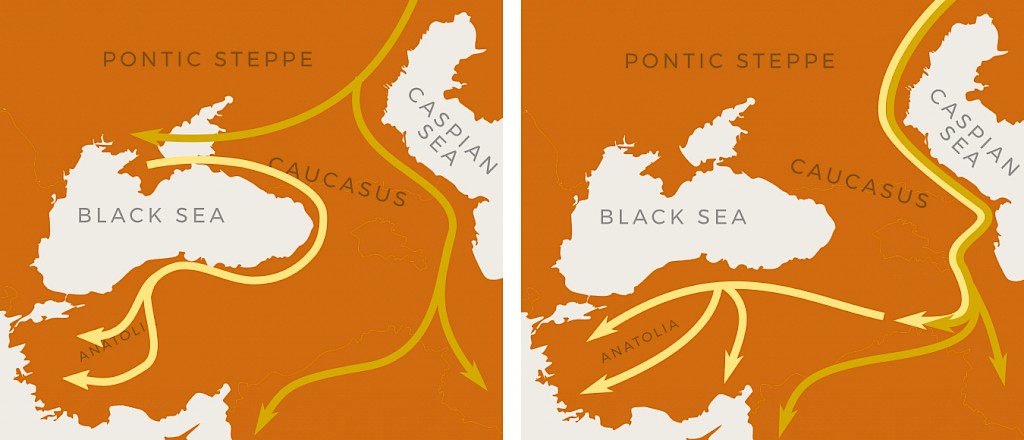

The Cimmerians fled, passing the Caucasus on the side of the Black Sea, and reached Anatolia. There, they raided the prosperous kingdoms of Phrygia and Lydia, until they were finally defeated by King Alyattes of Lydia (r. 610–560 BC), who went on to conquer all the lands west of the River Halys.

The Scythians pursued the Cimmerians, passing the Caucasus on the side of the Caspian sea, reaching Iran. When the Scythians found out that the Cimmerians had taken another route, they decided to attack the Median kingdom ruled by Cyaxares (r. 625–585 BC) instead. The Scythians ruled the region for 28 years, conducting raids as far as Palestine, until they were finally defeated by Cyaxares, who reclaimed his throne and went on to conquer all the lands east of the River Halys.

This is the story that Herodotus tells us about the Cimmerians and the Scythians (Hdt. 1.103–106 and 4.11–12). It is a remarkably detailed account, certainly when one considers that the events took place at least two centuries before Herodotus’ own time. Before the discovery of Akkadian cuneiform sources, it was generally accepted as true.

This attitude was strengthened when the Akkadian cuneiform sources confirmed the presence of Cimmerians (Gimirri) and Scythians (Ishkuza) south of the Caucasus. Classicists have been interpreting the Akkadian cuneiform sources on the Cimmerians and the Scythians through the lens of Herodotus ever since.

Similarly, archaeologists have tried to find evidence for the Cimmerian and Scythian migrations as described by Herodotus.However, there are some problems with Herodotus’ account that cannot be overlooked.

The archaeological record

First of all, Herodotus claims that there was a thriving Cimmerian culture north of the Black Sea before the arrival of the Scythians. This has led archaeologists to apply the name “Thraco-Cimmerian” to a distinct type of material culture that existed north of the Black Sea and along the banks of the Danube in the ninth to seventh centuries BC.

This material culture consist mostly of luxurious grave goods, including bronze weapons, bronze horse bridles, and bronze jewelry. The cultures most often associated with these “Thraco-Cimmerian” finds are the Chernogorivka culture and the Novocherkassk culture. At first glance, these cultures appear to be good candidates for a Cimmerian homeland. The problem, however, is that no “Thraco-Cimmerian” finds have been found south of the Caucasus.

There is also still some discussion on the question of a Scythian migration from Central Asia. Those who support this hypothesis point out that the first examples of Scythian art have been found in Southern Siberia around 900 BC, reaching the area north of the Black Sea no earlier than the eighth century BC. Those who oppose this hypothesis claim that Scythian art developed naturally from the Chernogorivka and Novocherassk cultures.

Scythian material culture, like “Thraco-Cimmerian” culture, consists mostly of richly decorated grave goods like weapons and horse gear. Unique to Scythian material culture, however, are its lavish use of gold and its impressive animal figurines. Unlike “Thraco-Cimmerian” material culture, Scythian art has, in fact, been attested in the region just south of the Caucasus and in northeastern Anatolia.

The presence of Scythian material culture and the absence of so-called “Thraco-Cimmerian” material culture south of the Caucasus has some interesting implications. First of all, it seems that the Scythian material culture found south of the Caucasus represents not only the Scythians proper, but also the Cimmerians. This, in turn, implies that the Cimmerians were closely related to the Scythians, possibly even a subgroup.

Furthermore, it also implies that the “Thraco-Cimmerian” material culture is not Cimmerian at all. This makes a Cimmerian homeland north of the Black Sea less plausible, unless we assume that the Cimmerians adopted Scythian art styles before migrating to Anatolia.

The route of the Cimmerians

In addition to the lack of “Thraco-Cimmerian” finds south of the Caucasus, there are some practical problems with the Cimmerian migration as described by Herodotus.

Firstly, in order for the Cimmerians to reach the Caucasus, they must have travelled in an easterly direction. This, however, would be quite illogical if the Scythians, who were attacking them, came from the east themselves. Secondly, the notion that the Cimmerians passed the Caucasus on the side of the Black Sea is problematic, as the terrain there is rugged and the coastal plain is very narrow. Although such a migration cannot be ruled out, the Scythian migration on the side of the Caspian Sea makes much more sense, in spite of what Herodotus himself claims (Hdt. 1.104). The coastal plain along the Caspian Sea is much wider.

A final problem with the route described by Herodotus is that Assyrian sources from the reign of Sargon II (r. 721-705 BC) mention the Gimirri (i.e. Cimmerians) as living near Uishdish, a Mannaean kingdom near Lake Urmia. From there, they attacked the kingdom of Urartu somewhere between 720 and 714 BC.

In order to reconcile this information with Herodotus’ account, one has to assume that the Cimmerians travelled from Colchis all the way to Lake Urmia, traversing the entire kingdom of Urartu before attacking the same kingdom from the southeast. Even if we assume that the nomadic Cimmerians were highly mobile, this is still unlikely. If they came from north of the Caucasus, they most likely travelled along the Caspian shore.

What do the Assyrian sources say?

Oracle texts from the reign of Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BC) again mention the Gimirri among the people of the Zagros region, along with the Mannaeans and the Medes. It is around this time the Gimirri start raiding regions further from their “home” near Lake Urmia.

In 679 BC, they attacked Cilicia and, in 676 BC, they turned to Phrygia. Finally, in the second half of the seventh century BC, they started to raid Lydia. These Anatolian activities of the Cimmerians have understandably become the focus of Herodotus’ account, but initially their main zone of activity appears to have been the northern Zagros.

The same oracle texts also mention the Ishkuza (i.e. Scythians). They state that Esarhaddon forged an alliance with Bartatua, king of the Ishkuza, probably in an attempt to counter the threat of Gimirri, Mannaean, and Median attacks. This Bartatua is known as “Protothyes” in the work of Herodotus.

The son of this Protothyes – Madyes – is said to have conquered the Medes and to have ruled Asia for 28 years, but there is no contemporary evidence for these claims. Perhaps the Ishkuza conducted raids against the Medes, who at that time were little more than a loose confederation of tribes. This may have given rise to the notion of a 28 year Scythian reign.

A tentative reconstruction

Considering these objections to Herodotus’ account, let us now try to reconstruct the real course of events.

First of all, it seems that the Cimmerians (Gimirri) and the Scythians (Ishkuza) were closely related. We may count them both among the “Scythic peoples”. The Gimirri were probably the first among these Scythic peoples to venture south of the Caucasus around 720 BC, arriving in Uishdish after passing the Caucasus on the side of the Caspian Sea. Around 680 BC they were followed by the Ishkuza.

In the 670s BC, king Esarhaddon of Assyria formed an alliance with king Bartatua of the Ishkuza, probably with the intent of keeping the tribes from the Zagros region in check. Bartatua then started raiding the Zagros region, targeting both the Gimirri and the Medes.

As a result, the Gimirri fled to Anatolia, where they continued to raid Phyrgia and Lydia. This is where the notion that the Scythians had driven the Cimmerians from their homeland may have originated.

Meanwhile, the Medes continued to fight Bartatua and his son Madyes, until they gained the upper hand under the leadership of Cyaxares.

The Cimmerian homeland

The question then remains how Herodotus came to conclude that the steppes north of the Black Sea were the original homeland of the Cimmerians. He even claimed that certain monuments and landmarks were named after them. Although there is no conclusive answer, several factors may have played a role.

The Cimmerians most likely did come from north of the Caucasus, although their specific place of origin probably differs from the one mentioned by Herodotus. The notion that the Cimmerians took the western route around the Caucasus may simply be the result of Herodotus’ wish to impose some kind of geographical symmetry on history:

- The Cimmerians took the western route around the Caucasus, raided the lands west of the River Halys and were defeated by King Alyattes of Lydia, who thus established his hegemony over the lands west of the Halys.

- The Scythians took the eastern route around the Caucasus, raided the lands east of the River Halys and were defeated by King Cyaxares of Media, who thus established his hegemony over the lands east of the River Halys.

A similar desire to impose symmetry can be seen when Herodotus wrongly claims that the courses of the Nile and the Danube run parallel to each other.

Finally, I should briefly discuss that a people called the Kimmeroi are named in Homer’s Odyssey. These Kimmeroi live in the far west, across the Ocean, in a misty land never touched by the sun. They appear to be purely mythical. The name Kimmeroi is perhaps derived from the Greek word kemmeros, which means mist. When the Greeks came into contact with a people named the Gimirri, however, and noted the similarity in name with Homer’s Kimmeroi, they began to conflate the two.

Perhaps it was this confusion with the Homeric Kimmeroi that led Herodotus to place the original homeland of the Cimmerians north of the Black Sea, at the edge of the known world. This way, a fictional homeland was invented for a people whose real homeland was unknown to the Greeks.

Further reading

Suggestions for further reading are listed below:

- R. Borger, Die Inschriften Asarhaddons, Königs von Assyrien, Archiv für Orientforschung Beiheft 9 (1956).

- U. Cozzoli, I Cimmeri, Studi pubblicati dall’istituto italiano per la storia antica 20 (1968).

- K. Deller, “Ausgewählte neuassyrische Briefe betreffend Urarṭu zur Zeit Sargons II”, in: Tra lo Zagros e l’Urmia (1984), pp. 97-104.

- I.M. Diakonov, “The Cimmerians”, in: Monumentum Georg Morgenstierne I, Acta Iranica 21 (1981), pp. 103-40.

- J.A.G. Kossak, “Von den Anfängen des skytho-iranischen Tierstils” in Skythika (1987), pp. 24-86.

- G.B. Lanfranchi, “Some New Texts about a Revolt against the Urarṭian King Rusā I”, Oriens Antiquus 22 (1983), pp. 124-35.

- G.B. Lanfranchi and S. Parpola, State Archives of Assyria I. The Correspondence of Sargon II, pt. 1 (1987).

- G.B. Lanfranchi and S. Parpola, State Archives of Assyria V. The Correspondence of Sargon I, pt. 2 (1990).

- M. Salvini, “La storia della regione in epoca urartea”, in: Tra lo Zagros e l’Urmia (1984), pp. 9-51.

- I. Starr, Queries to the Sun God: Divination and Politics in Sargonid Assyria (1990).

- A.I. Terenozhkin, Cimmerians (1983).